This is the second article in the series, following our first blog in Dec 2023:

https://www.sigarch.org/tuning-the-symphony-of-heterogeneous-memory-systems/

Modern applications are increasingly memory hungry. Applications like Large-Language Models (LLM), in-memory databases, and data analytics platforms often demand more memory bandwidth and capacity than what a standard server CPU can provide. This leads to the development of coherent fabrics to interconnect more memory with cache coherence support, such that workloads can benefit from large memory capacity with ideally not much effort to modify the code.

But is it truly trivial for workloads to adopt such heterogeneous memory systems? Are there any hidden caveats behind the pipedreams of future memory systems? And if one decided to build such a heterogeneous memory system, what are some important factors to consider before building a cluster of such systems?

To answer such questions, we studied a wide range of coherent fabrics, namely Compute Express Link (CXL), NVLink Chip-to-Chip (NVLink-C2C), and AMD’s InfinityFabric. In terms of architecture reverse engineering, performance characterizations, and performance implications to emerging workloads.

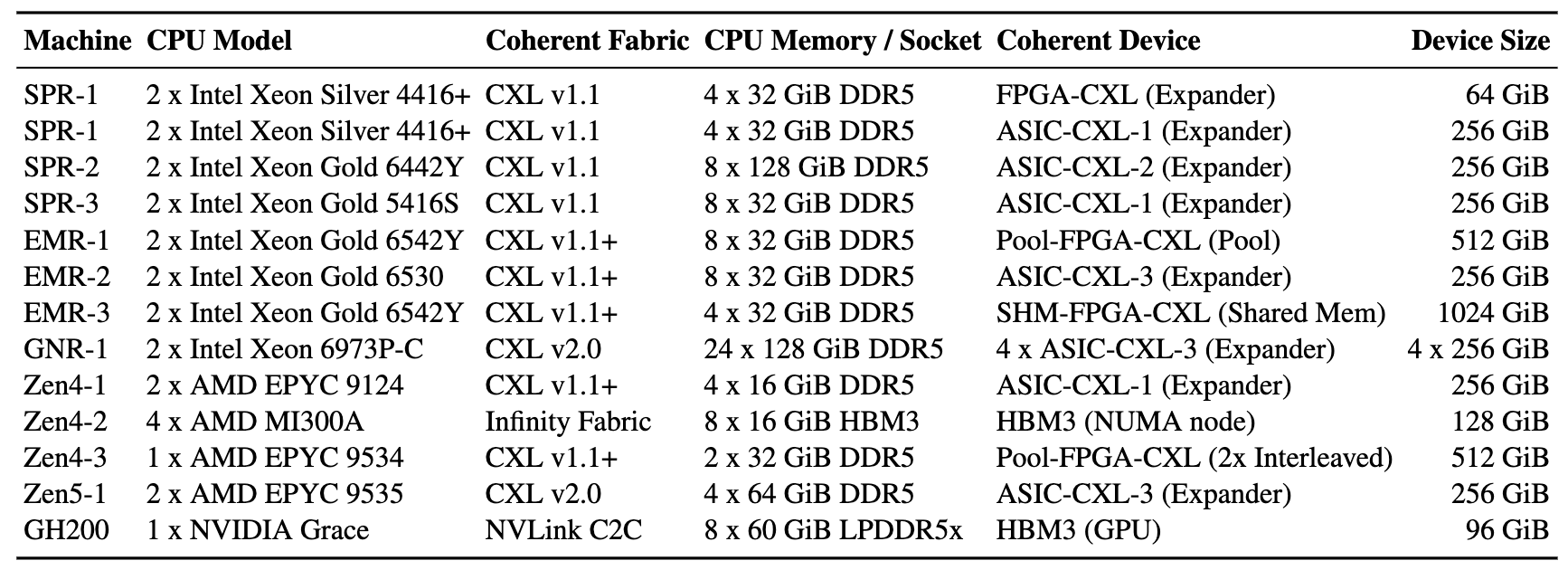

This work is made possible with 8 PhD students from 4 UCSD research groups working over 1.5 years, with wide industrial collaborations. Together we measured 13 server systems, across 3 CPU vendors with a wide range of CPU generations, 3 types coherent fabric links, 5 device vendors, and multiple system configurations (including local vs. remote NUMA, Sub-NUMA clustering mode, interleaved mode, etc.).

We have shared our detailed observations on ArXiV, and open sourced our benchmarking suite on GitHub which runs on all the above-mentioned systems even including non-CXL systems like NVIDIA GH200. This blog article focuses on CXL, which has recently witnessed a broad attention. Please refer to our paper for more details on other types of coherent fabrics.

1. Compute Express Link (CXL)

CXL today is widely available, with latest server CPUs from Intel and AMD supporting memory expanders from various vendors. But given such options, one needs to decide if they need CXL, and how to build a CXL system.

1.1 Who Should Use CXL?

The core value propositions of CXL-based memory expansion are:

- Massive Capacity Expansion: CXL allows for the addition of hundreds of gigabytes, or even terabytes, of extra memory through the server’s PCIe slots.

- Targeted Bandwidth Expansion: In scenarios where the main memory channels are saturated but PCIe lanes sit idle, CXL can increase the total system bandwidth. And CXL is superior to directly-attached DIMMs in terms of bandwidth per CPU pin. This is particularly beneficial for workloads that are not acutely sensitive to latency.

If any of these are currently limiting your workload, then CXL might be worth looking into. And the rest of this article may help you with more detailed suggestions.

1.2 How to architect a CXL-based Machine?

Before you start to spec your machine with CXL, there are a few things to consider:

1.2.1 Latency Tax

The first principle of CXL is that it is slower than the Local DRAM with accesses being 50% to 300% slower. Measurements show that while a typical local DIMM access might take around 100 ns, an access to a modern ASIC-based CXL device falls in the 200-300 ns range. Early-generation FPGA-based CXL prototypes are even slower, with latencies around 400 ns.

CXL has high latency tax, however alternatives to CXL are even worse. To put CXL’s latency in context, here is a comparison of different memory/storage technologies:

| Metric | Local DRAM (DIMM) | Local CXL Memory (ASIC) | NVMe SSD |

| Typical Latency | Lowest (~80-120 ns) |

Medium (~200-300 ns) |

Highest (10,000+ ns) |

| Peak Bandwidth | Highest (200+ GB/s) |

Medium (~30 GB/s per device with 16 lanes) |

Lower (~7-14 GB/s) |

| Max Capacity | Limited by DIMM slots | High (Terabytes) | Highest (Many TBs) |

| Recommended Use Case | Hot Data, Performance | Warm Data, Capacity Tier | Cold Data, Storage |

Rule of the thumb: It is important to remember that CXL is a new tier of memory, not a DRAM replacement! Don’t think of CXL as a way to get more of fast memory. Think of it as a way to get faster access to massive capacity.

1.2.2 Bandwidth: Scalable but with Limits

A single CXL memory expander using 8 CXL 2.0 lanes (each CXL lane takes one PCIe lane) provides up to 32 GiB/s of additional memory bandwidth. Modern AMD servers such as AMD Turin provide up to 64 CXL lanes, offering up to 250 GiB/s of additional memory bandwidth.

In practice, we measured about 25-30 GiB/s of memory bandwidth of a single 8-lane CXL memory expander on real systems. Thus a 64 CXL-lanes CPU can support 200~240 GiB/s of CXL bandwidth.

2. The 5 Essential Rules of CXL Programming

Rule #1: Pin Your Workloads, Especially on Earlier Intel CPUs

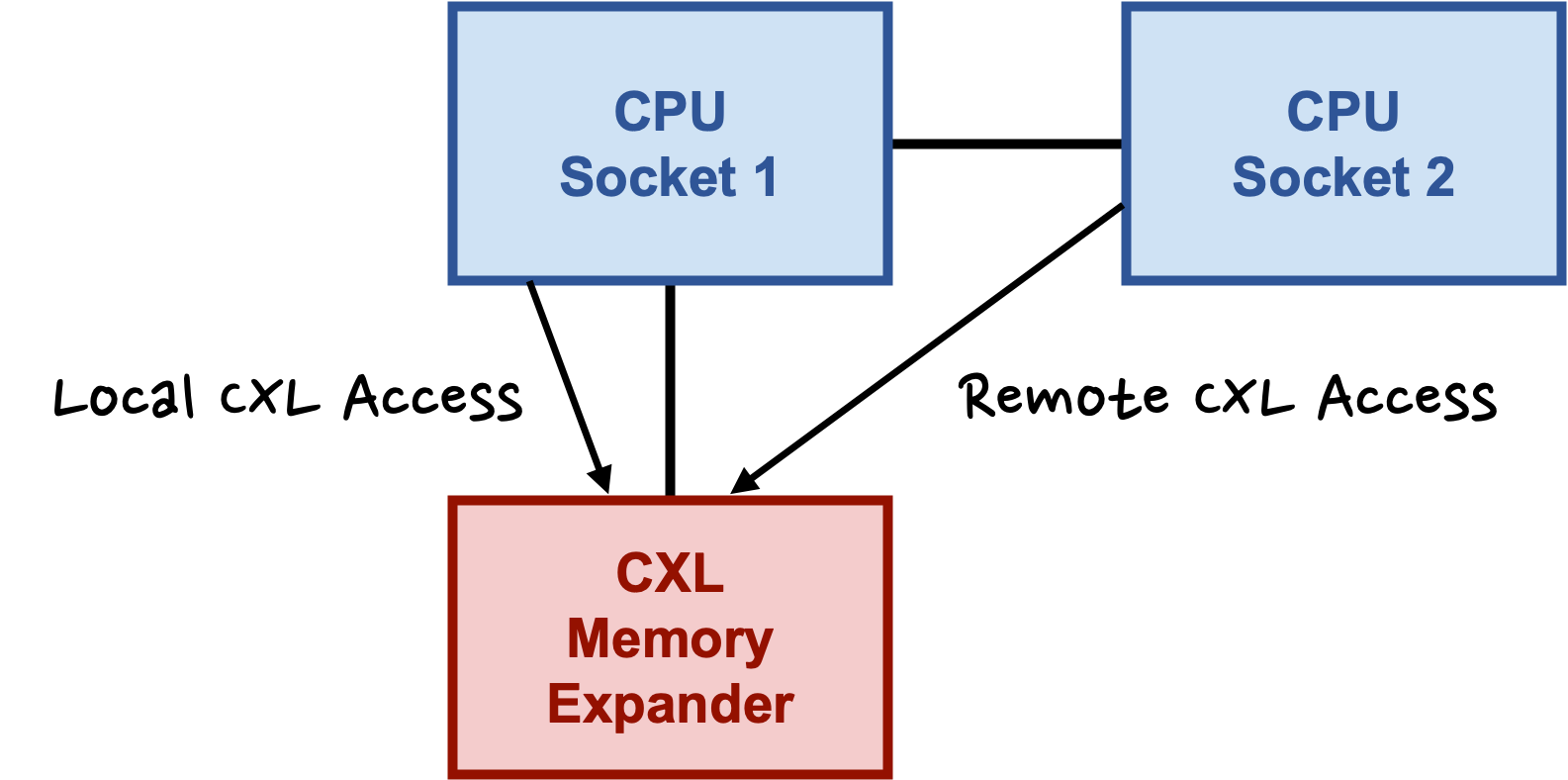

To avoid limiting the workloads to a fraction of the available Last-Level Cache (LLC), Intel CPU users should strongly consider pinning workloads that access CXL memory to the local socket using tools like numactl.

The reason is that on the tested Intel Sapphire Rapids (SPR) and Emerald Rapids (EMR) CPUs, an application accessing CXL memory remotely is restricted to only a fraction of its local CPU’s LLC which is as little as 1/8th of the total cache on SPR and 1/4th on EMR. In contrast, remote access to standard DIMM memory can utilize the full LLC. However, the tested AMD Zen4 (we only have a single socket Zen5 so cannot verify whether Zen5 is affected) and the new Intel Granite Rapids (GNR) systems did not exhibit this behavior, showing symmetric cache utilization for both local and remote CXL access. For system architects, it means services must be designed with an explicit awareness of this physical topology to avoid catastrophic performance degradation.

|

|

|

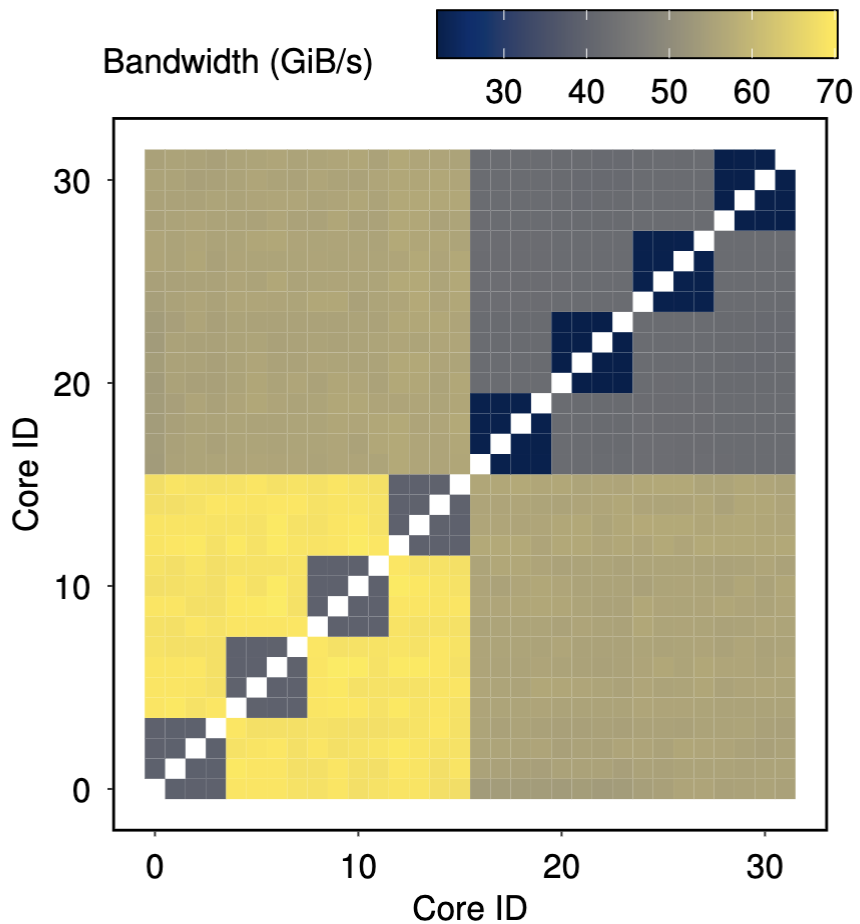

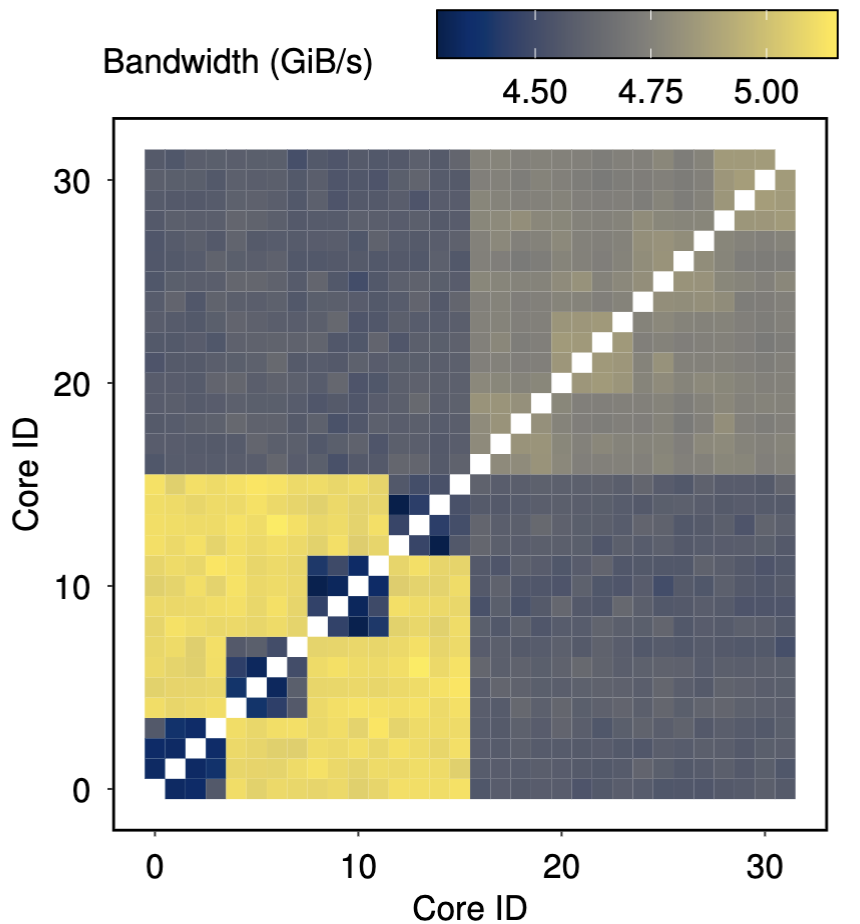

Zen4-1-ASIC-CXL-1: DRAM bandwidth. |

Zen4-1-ASIC-CXL-1: CXL bandwidth. |

|

Running two threads of bandwidth test on different cores, using Zen4-1 with ASIC-CXL-1 (refer to Table 1 for hardware details). |

|

Workload pinning should also take chiplet performance into consideration. As illustrated in the above figure, chiplet architecture impacts the bandwidth of accessing not just DRAM but also CXL; accesses originating from cores within the same chiplet group have a lower bandwidth. While the above example is from Zen4, other chiplet-based CPUs generally have similar performance characteristics.

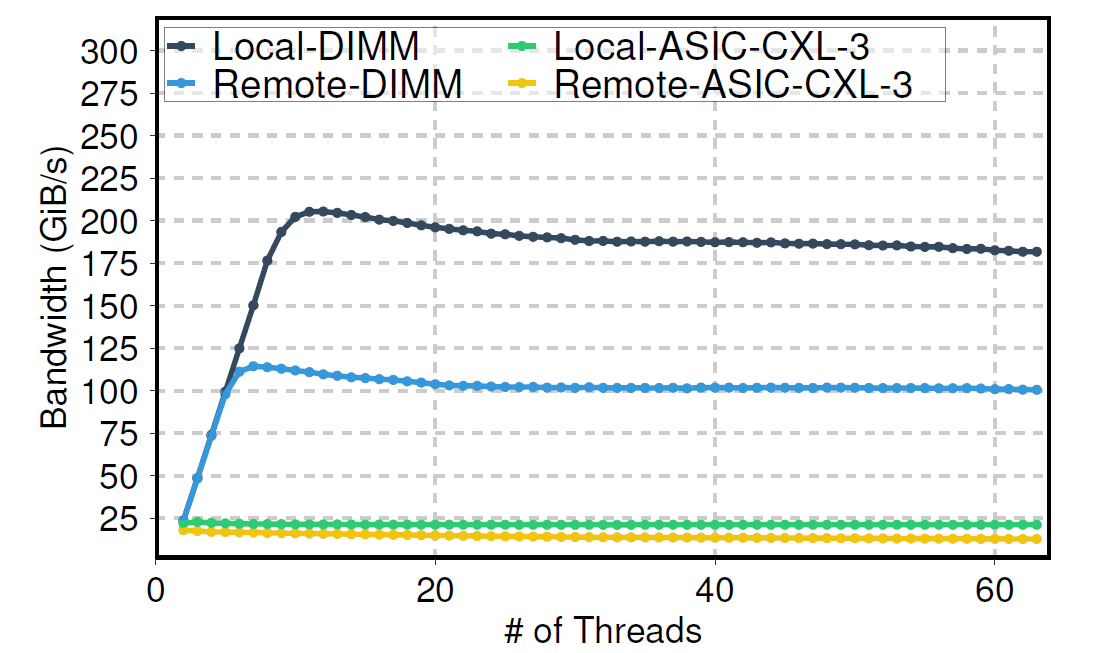

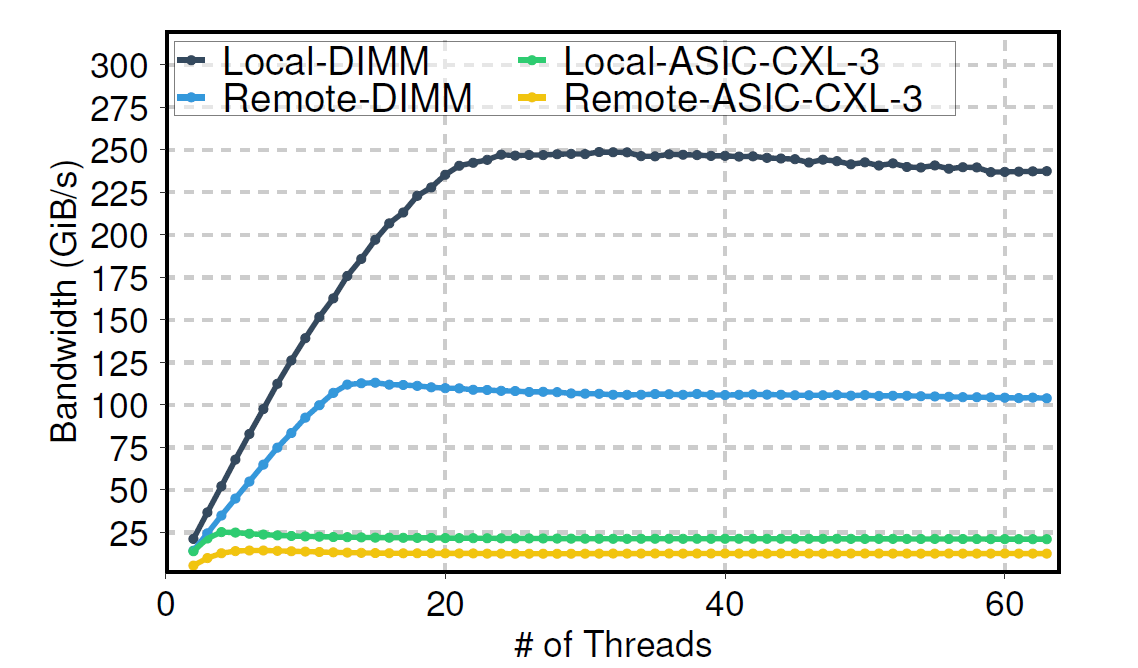

Rule #2: Asymmetric Read/Write Performance

We observed a critical performance asymmetry on the tested AMD platforms. While load (read) bandwidth scaled with thread count, the store (write) bandwidth for ASIC CXL devices remained flat and low, regardless of the number of threads. This indicates a potential “performance asymmetry” for certain workloads on these platforms, where a very small number of cores can achieve the peak bandwidth with stores vs. loads.

|

|

||

|

Store performance DIMMs vs CXL memory expander. |

Load performance DIMMs vs CXL memory expander. |

||

|

|||

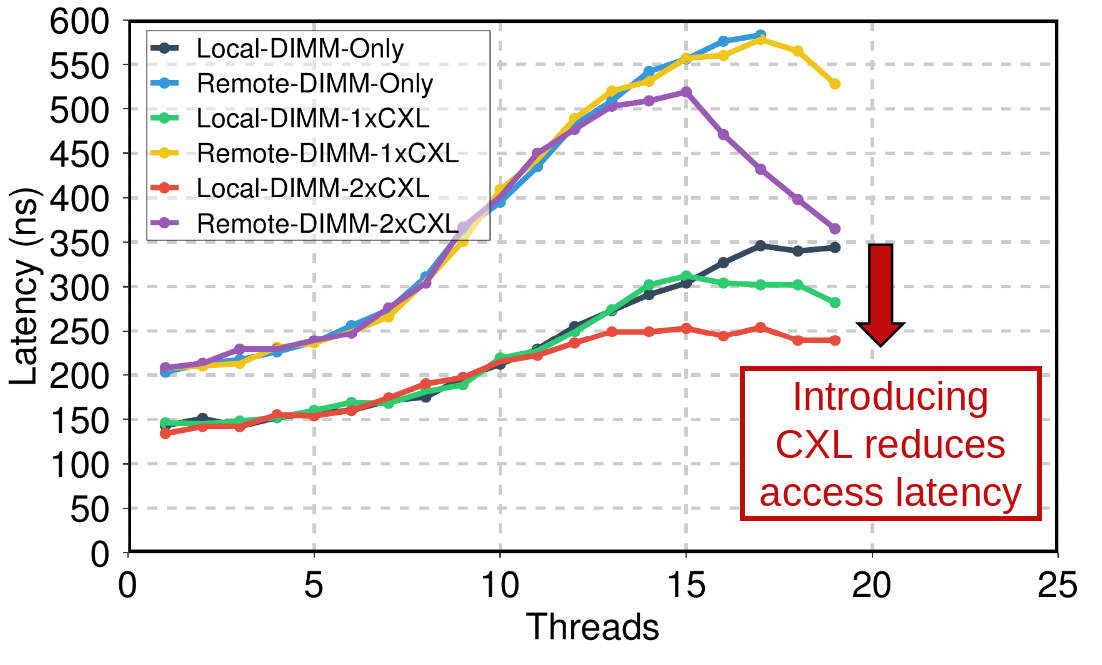

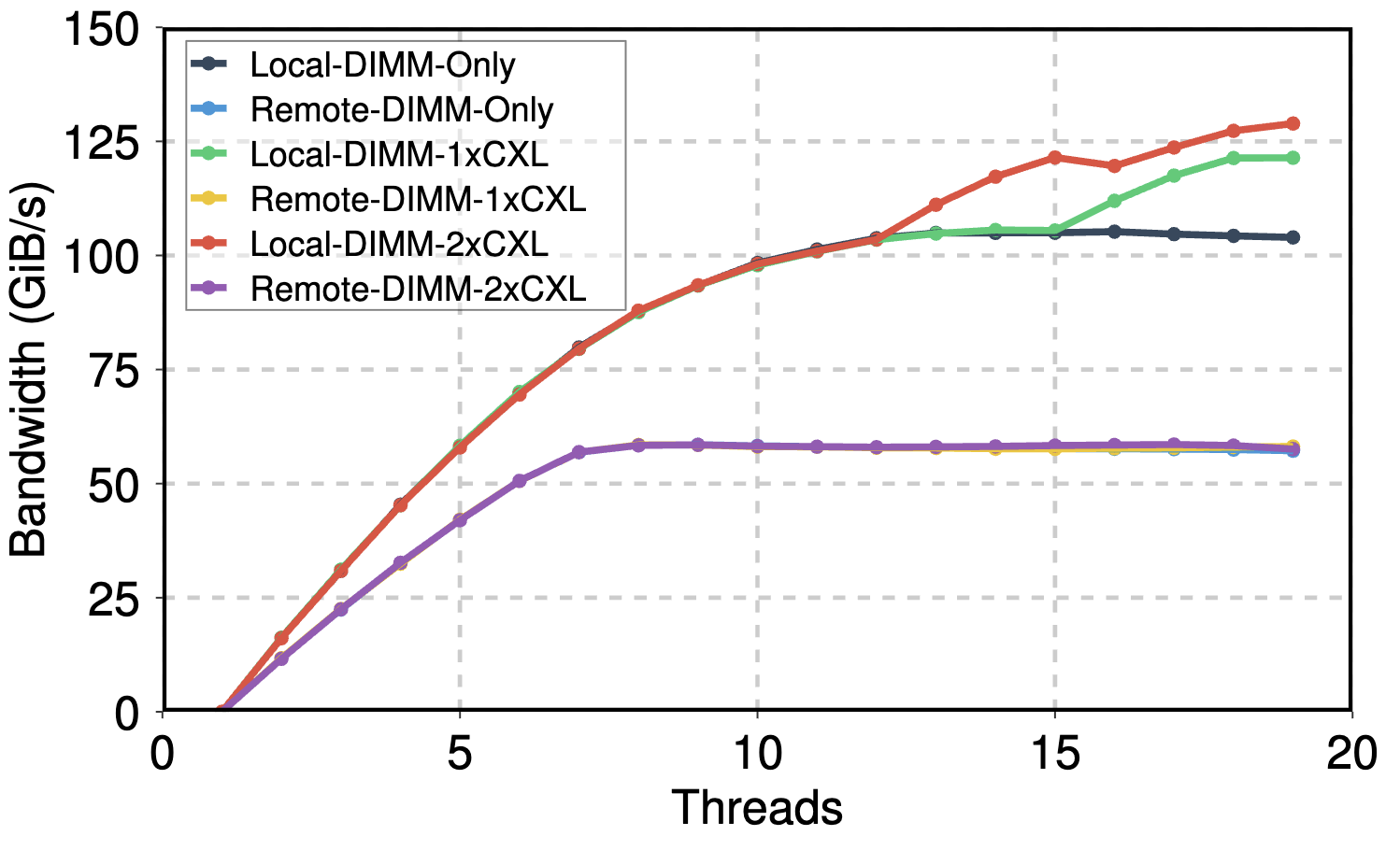

Rule #3: Introducing CXL Memory Reduces the Overall Memory Access Latency

Average load access latency scaling with threads. |

Total load bandwidth scaling with threads. |

|

Latency and bandwidth scaling with threads shows that DIMMs+CXL not only increased the total available memory bandwidth, but also decreased the average memory access latency. |

|

Adding CXL memory alongside DDR DIMMs lowers overall system memory latency even though CXL memory itself is slower. This happens because the extra bandwidth from CXL prevents DRAM channels from saturating, reducing queuing delays and shortening average access time.

In experiments on an Intel SPR system with two CXL memory expanders on the same socket, we found:

- Latency improvement: Once CXL devices were active, total memory latency dropped compared to using only DIMMs. E.g., the “Local-DIMM + 1xCXL” has lower read latencies than using solely local DIMMs.

- Bandwidth extension: A single CXL device added roughly 17 GiB/s of bandwidth, while two devices offered about 25 GiB/s. This is below their combined theoretical 50 GiB/s peak, indicating partial utilization.

On the remote socket, CXL memory did not increase bandwidth. This is likely due to UPI saturation, but it still reduces latency when used with DIMMs.

Rule #4: Which CPU Architecture to Pick?

The bandwidth and latency performance of CXL Memory Expanders are significantly influenced by the CPU microarchitecture. We find AMD CPUs in general can saturate the CXL device bandwidth, while Intel’s earlier generations (SPR and EMR) are sub-optimal; but the recent GNR generation reaches parity with AMD.

Intel and AMD CPUs demonstrate a similar bandwidth accessing local memory. However, Intel’s SPR and EMR processors exhibit relatively lower bandwidth in remote memory access compared to local access, while the latest GNR fixed the issue. In terms of latency characteristics, Intel CPUs generally offer a lower latency than AMD processors.

Both CPU architectures exhibit a common phenomenon whereby latency increases dramatically when approaching a maximum bandwidth utilization. This represents a typical trade-off characteristic that occurs during memory system saturation and constitutes an important performance consideration when implementing CXL Memory Expander solutions.

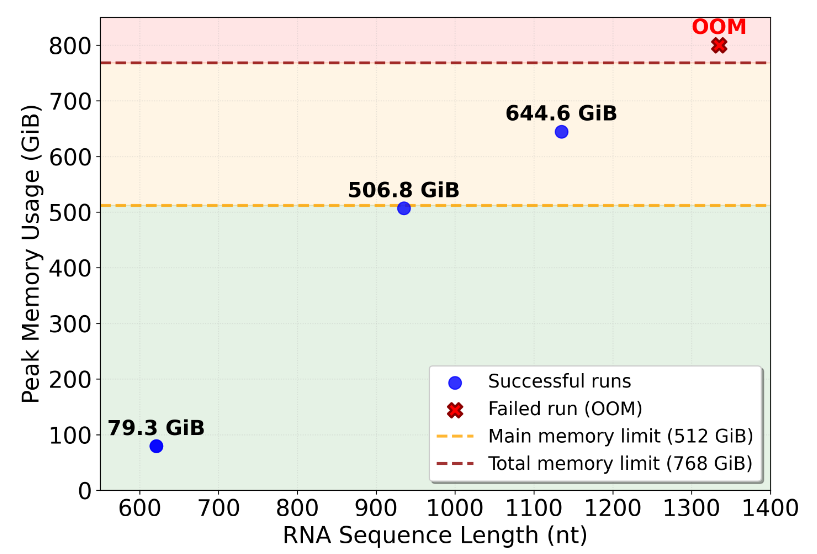

Rule #5: Capacity Expansion Enables Complex AI-based Scientific Discovery Like AlphaFold3

CXL memory makes it tempting for many memory-hungry workloads, and among which we find AI-based scientific workloads an interesting use case. Such workloads consume a large amount of memory capacity and require good enough bandwidth, while the end-to-end execution time is dominated by CPU-side operations rather than GPU. CXL is the drop-in solution for them.

In our experiments with AlphaFold3 accessing CPU DIMM memory: even when most inputs run within system memory capacity, heavy inputs including RNA will require hundreds of gigabytes. On DIMM-only systems these inputs fail with out-of-memory errors, but with CXL memory expanders they complete successfully. Although CXL introduces additional latency, its impact was secondary; capacity expansion was the decisive factor for enabling these workloads.

This is a clear example of a broader pattern: scientific workloads are often deployed on HPC systems already tuned for expected requirements, yet unusually large inputs can break those assumptions. In such situations, CXL memory provides a flexible alternative by expanding capacity on demand without rebuilding servers or modifying applications.

Conclusions

We are entering the era of heterogeneous computing, where the memory system is getting more heterogeneous with the addition of coherent fabrics like CXL. Our research revealed that such systems have unconventional performance characteristics, and programmers have to carefully consider such characteristics to achieve optimal performance.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the PRISM and ACE centers, two of the seven centers in JUMP 2.0, a Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC) program. We would also like to acknowledge Microsoft, Giga Computing, Samsung Memory Research Center, and National Research Platform for providing access and support for various servers.

About the authors:

Zixuan Wang got his PhD from the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research spans across architecture and system, with a focus on heterogeneous memory system performance and security.

Suyash Mahar got his PhD from the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research focuses on cloud computing with focus on memory and storage systems.

Luyi Li is a PhD student in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research focuses on exploring vulnerabilities, designing protections and optimizing performance for CPU architecture and memory systems.

Jangseon Park is a PhD student in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research interests are in heterogeneous memory system architecture for AI systems with emerging memories.

Jinpyo Kim is a PhD student in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research focuses on memory-centric optimization and energy-efficient computing for heterogeneous AI/ML architectures.

Theodore Michailidis is a PhD candidate in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research interests lie at the intersection of memory, operating and datacenter systems.

Yue Pan is a PhD student in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research interest lies in computer architecture, memory, and system designs for high-performance applications.

Mingyao Shen got his PhD from the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research is in storage and memory system performance. This work was done while Mingyao was with UCSD.

Tajana Rosing is a Fratamico Endowed Chair of Computer Science and Engineering and Electrical Engineering at University of California, San Diego. Her research spans energy-efficient computing, computer architecture, neuromorphic computing, and distributed embedded systems. She is an ACM and IEEE Fellow.

Dean Tullsen is a Distinguished Professor in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. His research focuses on computer architecture, with contributions spanning on-chip parallelism (multithreading, multicore), architectures for secure execution, software and hardware techniques for parallel speedup, low-power and energy-efficient processors, servers, datacenters, etc.

Steven Swanson is a Professor in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego and holds the Halicioglu Chair in Memory Systems. His research focuses on understanding the implications of emerging technology trends on computing systems.

Jishen Zhao is a Professor in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at University of California, San Diego. Her research spans and stretches the boundary across computer architecture, system software, and machine learning, with an emphasis on memory systems, machine learning and systems codesign, and system support for smart applications.

Disclaimer: These posts are written by individual contributors to share their thoughts on the Computer Architecture Today blog for the benefit of the community. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal, belong solely to the blog author and do not represent those of ACM SIGARCH or its parent organization, ACM.